It was the summer of 2012 when I first met Kulada Kumar Bhattacharya at his residence near Panbazar, Guwahati. I was working on a feature on radio plays for the Sunday supplement of a now-defunct local English daily and wanted to know about the legacy of audio theatre in Assam, as well as his contribution to Akashvani Guwahati. Clearly, his oeuvre warranted a full-page story in itself, but nevertheless, I stuck to my assignment. I had spoken to him over the phone a few days before the meeting and he had suggested I visit him that afternoon.

Quiet, nondescript and nostalgia-inducing – his residence was an old-style building tucked in the heart of Guwahati. As I opened the gate and mentioned his name, somebody pointed toward the stairway on the side. I walked up and was instantly charmed by what unfolded in front of me. It was a porch covered with low-slung potted plants, flanked by a smattering of cane chairs – a sight once synonymous with the traditional Assam-type homes but now a rarity.

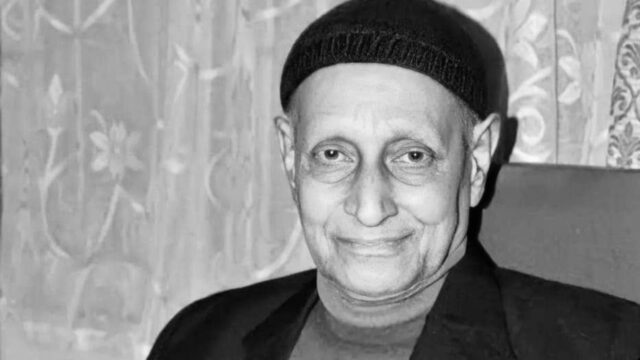

An old black-and-white picture secured in a wooden frame hung on the opposite wall. Moments later, Kulada Kumar came out and greeted me with a gentle smile. He was no ordinary man, yet in my first meeting I found him unassuming and curious like a child. A luminous presence in the northeastern state’s literary and cultural landscape, the legendary actor-director’s body of work spanned decades traversing cinema, theatre, radio and television. He’s also revered as a dynamic voiceover artist. In 2023, he won the ‘Best Narration/Voice Over Award’ at the 69th National Film Awards for his contribution to filmmaker Kripal Kalita’s documentary Hati Bondhu (Friends of Elephants).

Known for his ingenuity, astuteness and abiding passion for the arts, the acclaimed stage and screen personality kept himself absorbed in work almost until his last days. Kulada Kumar died in a private hospital in Guwahati on November 1, following a brief illness. He was 91. Last seen in writer-director Sourav Baishya’s 2021 film Khyonachar, he played the character of a rather reclusive and despondent grandfather, named Hitu Prasad. Before that, he played a crucial role in award-winning filmmaker Rima Das’ coming-of-age drama film Village Rockstars, which was selected as India’s official entry to the 91st Academy Awards.

That afternoon, as we sat down to talk, he told me, “I am surprised a young journalist such as yourself is taking interest in writing about radio plays, out of all.” I was already four-five years into journalism at that time, and his remark made me feel both flattered and anxious at once. While I was thrilled to be working on an ‘interesting’ story, it also made me worry about what if I failed to do justice to it. Nonetheless, after a brief introduction about myself, I began to fire away.

He began with recollecting his experience of recording radio plays sitting in the studios at All India Radio (AIR) Guwahati back in the day. Located in Chandmari, the first broadcast from the Guwahati station was made in July 1948. Kulada Kumar said, “Earlier, we used to sit around the microphone with a copy of dialogues in hand. It used to be the most crucial and interesting part of recording radio plays. In fact, it was quite amusing how sometimes an actor would deliver his dialogues standing in a corner of the studio just to give an impression that he is somewhere far away.”

For him, it was both a liberating and fascinating experience. “The play can be set just about anywhere – in an aeroplane, down a goldmine, on a ship, or even within the confines of somebody’s mind. Everything is made vivid with a strong script, profound dialogues, and catchy sound effects,” he elaborated. A graduate from the New Era Academy of Drama and Music in London, who later joined the British Drama League, the then 79-year-old cultural icon was a treasure trove of information and anecdotes.

After coming back from London, Kulada Kumar joined Akashvani Guwahati in 1962, as the Producer-in-Charge of Drama. It was during his tenure that the Guwahati station restored several classic Assamese plays. So much was the popularity that they even began a signature show, called Naat Chora, dedicated to old and new plays.

During our conversation, he spoke of a time in the history of Assam when radio plays were quite the rage, be it in towns or remote villages. For years, the charm of audio dramas kept listeners, both young and old, glued to their transistors. Stalwarts like Kulada Kumar not only loved the medium but also meticulously carried out the responsibility of penning and producing plays that bewitched many minds.

Walking down memory lane, he said, “Until the emergence of television in the mid-1980s, dramas were counted among the most widely popular programmes on radio. Eminent personalities like Lakhyadhar Choudhury, Arun Sarma, Dr Bhabendra Nath Saikia, Satya Prasad Barua, Phani Talukdar, Mohendra Borthakur and Narain Bezbaruah were as much involved in radio plays as they were in writing, directing and performing dramas on stage. Naba Sharma’s plays also attracted many listeners. Young artists were enthusiastic about lending their voice to different roles while aspiring writers competed with each other to put words together, creating some of the most intriguing scripts.”

According to him, those plays touched upon almost all aspects of life – socio-economic, science as well as pure fiction. Comedy shows, like Nukuwai Bhal by Durgeswar Borthakur, were also quite popular among the masses, while performances based on literary gems like Shakespeare’s Othello and Hamlet never failed to baffle listeners. During his prime, Kulada Kumar often worked together with doyens like Arun Sarma, Dr Bhabendra Nath Saikia, and Mohendra Borthakur. His most prominent collaborative projects included the Assamese adaptations of Oedipus Rex, Ben Hur, The Merchant of Venice and The Seagull, along with Yayati, Parasuram, Mrichchhakatika, Bonhaah, Tirtha and Matir Garih, among others. For a brief period, he even performed in Delhi, working alongside veterans like Habib Tanvir.

Apart from Khyonachar and Village Rockstars, Kulada Kumar’s other noteworthy performances in films included Raamdhenu (2011), Prabhati Pokhir Gaan (1992), Chik Mik Bijuli (1969), Lotighoti (1966) and Shakuntala (1961), together with Dikchow Banat Palaax (2016), Cactus (2016) and Surjasta (2013), in which he appeared as himself.

That day before I left his place, he handed over two photographs of himself sitting in the AIR Guwahati studio, so that I can use them along with the feature. Had it been now, I would have probably just captured those on my phone and not actually brought back the physical copies with me. I remember ringing him up again after the story was published in the July 1 edition of the newspaper’s Sunday Magazine. He was pleased to read the piece and suggested I write more about radio plays, maybe even do a series on them. He felt it was important for the younger generation to understand the legacy of these literary pieces. I couldn’t agree more. However, as fate would have it, the publication closed down a few months later, and I shifted to Bengaluru to find another job. I never met Kulada Kumar Bhattacharya again. His two black-and-white photographs remained with me… As a memory of that luminous June afternoon, spent in the company of a brilliant man.